Ogallala Aquifer’s dramatic drying sows deep concerns for agriculture

– – – –

The Ogallala Aquifer across the region has dropped about 325 billion gallons every year for at least the past four decades. To put that number into perspective, the roughly 1-foot annual drop in the aquifer is more than enough to supply all of Lubbock’s municipal water needs for 25 years.

And it has dropped about that amount every year since 1969, according to High Plains Underground Water District data analyzed by the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, which is owned by Morris Communications, the parent company for The Topeka Capital-Journal.

In all, across the district’s 16 counties, the aquifer has fallen about 40 feet, a decline of roughly 44.9 million acre-feet since 1969.

Primarily used for irrigation, the aquifer is critical to the region where agriculture represents about 30 percent of the economy. Agriculture’s direct economic impact for the High Plains is upward of $3 billion annually.

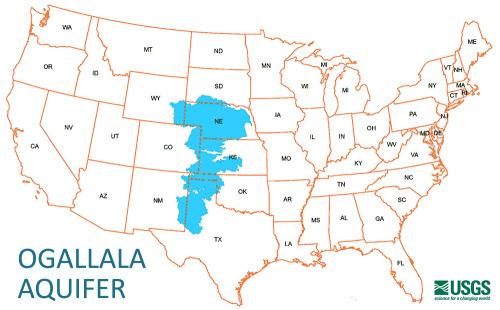

As vast as the High Plains aquifer is — it spans eight states and holds nearly 3 billion acre-feet of water — it could still run dry. A Kansas study last year estimated it could in less than 50 years. It likely will be sooner here.

OGALLALA STORAGE

■ The Ogallala Aquifer holds nearly 3 billion acre-feet of water.

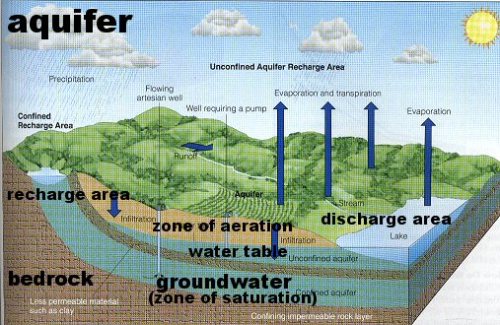

■ That water isn’t distributed evenly, and the aquifer doesn’t recharge the same everywhere. The stretches in Nebraska, for example, recharge with rainfall the most quickly.

■ Overall, the Ogallala has had about an 8 percent decline over the past six decades. In Texas, the Ogallala has dropped 150 million acre-feet during that time, accounting for roughly 60 percent of the overall decline.

■ From 2009 to 2011, the water table in Texas alone dropped 4.5 million acre-feet while it dropped 2.8 million over eight states.

What the U.S. Geological Survey estimates the Ogallala has in storage

■ Predevelopment in the 1950s — 3.20 billion acre-feet

1980 – 3.25 billion acre-feet

2000 – 2.98 billion acre-feet

2010 – 2.96 billion acre-feet

“When anybody tells me it’s going to last for 50 years, I just laugh,” said Lucia Barbato, associate director at the Center for Geospatial Technology at Texas Tech. “How long the aquifer lasts depends on where you are.”

Across the district, the aquifer already has dropped below the minimum depth for large-scale irrigation in portions of six counties, including Lubbock. Four other counties have fewer than 15 years before running out of groundwater, according to the center’s projections.

“Certainly, the magnitude of the decline is greatest in Texas,” said Virginia “Ginny” McGuire, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Nebraska. “You’re still using water at a much faster rate than it’s being recharged.”

Rapidly declining

That nearly 45 million-acre-foot decline in the Ogallala Aquifer equates to about 14.6 trillion gallons of water over 45 years.

That is enough — if the average American uses, conservatively, about 69 gallons a day — to meet the Lone Star State’s entire municipal water needs for roughly 20 years.

An acre-foot of water is used to describe large water resources such as river flows and reservoirs. It is the equivalent of 1 acre of surface area covered by water 1 foot deep — 325,853 gallons. The aquifer decline is larger than Lake Mead, which filled to capacity is roughly 28.9 million acre-feet. Lake Mead is the man-made reservoir in Nevada that supplies Las Vegas.

As staggering as the decline is, what is actually used to irrigate roughly 1.7 million acres of farmland throughout the district is likely much more.

No one knows with certainty how much water has been mined from the Ogallala. Most agree, though, that groundwater irrigation has been extensive, particularly in the Texas High Plains.

The reason for the ambiguity is complicated. Part of the answer is in what is actually being measured — how much is in irrigation wells. The High Plains district isn’t yet measuring how much water is taken out of the Ogallala.

This distinction is important because of the second reason for the uncertainty. The Ogallala Aquifer moves — albeit slowly — about a foot a day from west to east, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

That means the district’s annual measurements could be the Ogallala settling and not a true level change but rather a redistribution of the water in the aquifer to areas that are being pumped.

In short, more water is used than is being measured, experts say.

“We just think there’s been more water pumped than they show as a decline,” said Bob Stewart, director of Dryland Agriculture Institute at West Texas A&M University in Canyon. “I actually think that there’s more water in the aquifer remaining than a lot of people say there is. The bad news is, we’re using it faster than we say we are.”

‘Not sustainable’

The Ogallala Aquifer is among the largest aquifers. It extends 174,000 square miles beneath portions of eight states from South Dakota to Texas in one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world. Growing concern over extensive irrigation has led to, among other things, a state-mandated regional approach to conservation that requires planners to craft strategies that include a desired future condition.

The goal for Lubbock and the region is 50 percent left in 50 years. The board recently drafted rules that would require producers to track and limit their use to help meet the district’s 50-50 goal and stave off possible further regulation from Austin, if nothing were done.

The district held public hearings July 29 in Levelland and Aug. 5 in Canyon. A vote on the proposed rule change could come as early as this week. No one can say how much of a difference this will make.

“They will have no trouble meeting the 50-50 because as wells go off line the aquifer will rise, but that’s not because the aquifer is recharging,” said Robert DeOtte Jr., civil and environmental engineering professor at West Texas A&M University. “It won’t be a real 50-50. It’ll be an apparent 50-50.”

Maps projecting depletion rates in the district by the Center for Geospatial Technology at Texas Tech estimate large swaths of Parmer, Castro, Lamb and Hale counties have fewer than 15 years of usable life left.

The region was built on agriculture. Irrigation made it more profitable. “What most people in this city don’t understand is their livelihood is connected to agriculture,” said Darren Hudson, director of Cotton Economics Research Institute at Tech.

Economic researchers at the institute estimate a third of the ag revenue would be lost with a return to dryland farming, which typically has lower yields.

“We should care that it’s dropping,” Hudson said. “It’s an important resource that we need to figure out how to hang on to it as long as we can. We want to get the most that we can out of it and make it last as long as we can because the regional economy is so dependent on this resource and what we produce from it.”

Less than 30 percent of the cropland overlying the aquifer is irrigated. But more than half of the counties where depletion is a threat to irrigated agriculture are in Texas, according to a 2012 Texas Tech report on the future of the Great Plains.

And of those 19 Texas counties, nine are within the High Plains Underground Water District. The counties where depletion could mean the end of irrigated agriculture have also had some of the greatest water-level declines in the past four decades.

Curtis Griffith, a third-generation farmer who leases farmland in Cochran and Terry counties that has been in his family since his grandfather migrated here in the 1920s, has seen the pumping capacity decline by 90 percent.

Wells that once produced 500 gallons per minute now give up 50 gallons per minute. The way Griffith sees it, the land and the water beneath it aren’t just his.

“I just feel like I’ve still got some responsibility to future generations to pass the land on in as good a shape as I can,” Griffith said.

The counties where irrigated agriculture is threatened are Bailey, Castro, Cochran, Hale, Hockley, Lamb, Lubbock, Lynn and Parmer.

“We know it’s a limited supply and we just have to manage it as best we possibly can,” said Steve Verett, executive vice president of Plains Cotton Growers. “Farming is not going to go away. It’s just going to be different.”